I often hear, or read a quote that grabs my attention. Some are witty, some prophetic, and some reflect the challenges in life. Regardless, I’d like to share one each week. Enjoy!

All is vanity, and discovering it–the greatest vanity — John Oliver Hobbes

The closest friends I have made all through life have been people who also grew up close to a loved and loving grandmother or grandfather–Margaret Mead

Just as soon as we make a good resolution, we get into a situation which makes its observance unbearable–William Feather

The holidays are welcome to me partly because they are such rallying points for the affections which get so much thrust aside in the business and preoccupations of daily life–George E. Woodberry

We live in a rainbow of chaos–Paul Cezanne

Chaos demands to be recognized before letting itself be converted into a new order–Hermann Hesse

Joy untouched by thankfulness is always suspect–Theodor Haecker

At the innermost core of all loneliness is a deep and powerful yearning for union with one’s lost self–Brendan Francis

I like to think of thoughts as living blossoms borne by the human tree–James Douglas

Revenge holds the cup to the lips of another but drinks the dregs itself–Josh Billings

The dead don’t die. They look on and help–D.H. Lawrence

I cling to my imperfection as the very essence of my being–Anatole France

As you get older it is harder to have heroes, but it is sort of necessary–Ernest Hemingway

Solitude is a wonderful thing when one is at peace with oneself and when there is a definite task to be accomplished–Goethe

Despair lames most people, but it wakes others fully up–William James

There is something in religion which can only be expressed through conduct–John Jay Chapman

How old would you be if you didn’t know how old you are?—Leroy “Satchel” Paige

Every man has two journeys to make through life. There is the outer journey,with its various incidents and the milestones… There is also an inner journey, a spiritual Odysey, with a secret history of its own–Dean William R. Inge

Spiritual rose bushes are not like the natural rose bushes; with the latter the thorns remain but the roses pass, with the former the thorns pass and the roses remain–Saint Francis De Sales

Heroes get remembered, but legends never die–Babe Ruth

Every man has his own destiny: the only imperative is to follow it, accept it, no matter where it leads him–Henry Miller

Some memories realities, and are better than anything that can ever happen to one again–Willa Cather

Memory is not just the imprint of the past upon us; it is the keeper of what is meaningful for our deepest hopes and fears–Rollo May

We do not know the true value of our moments until they have undergone the test of memory–Georges Duhamel

A good vacation is over when you begin to yearn for your work–Dr. Morris Fishbein

There is nothing that war has ever achieved we could not better achieve without it–Havelock Ellis

It is all right for beasts to have no memories; but we poor humans have to be compensated–William Bolitho

A mother never realizes that her children are no longer children–Holbrook Jackson

Love is but the discovery of ourselves in others, and the delight in the recognition–Alexander Smith

The man who fails because he aims astray or because he does not aim at all is to be found everywhere–Frank Swinnerton

Sometimes there is no next time, no time-outs, no second chances. Sometimes it’s now or never–Alan Bennett

War makes strange creatures out of us little routine men who inhabit the earth–Ernie Pyle

You never realize death until you realize love–Katherine Butler Hathaway

All men have in them an instinct for conflict; at least, all healthy men–Hilaire Belloc

It is nothing short of genius that uses one word when twenty will say the same thing–David Grayson

Rightly to perceive a thing, in all the fullness of its qualities, is really to create it–C.E. Montague

Time is a storm in which we are all lost–William Carlos Williams

Most of us can remember a time when a birthday–especially if it was one’s own–brightened the world as if a second sun had risen–Robert Lynd

The community stagnates without the impulse of the individual. The impulse dies away without the sympathy of the community–William James

Once your children are grown up and have children of their own, the problems are theirs, and the less the older generation interferes the better–Elanor Roosevelt

The closest friends I have made all through life have been people who also grew up close to a loved and loving grandmother or grandfather–Margaret Mead

In any given moment, we have two options: to step forward into growth or step backward into safety–Abraham Maslow

Time is a storm in which we are all lost–William Carlos Williams

Duty does not have to be dull. Love can make it beautiful and fill it with life–Thomas Merton

Whenever people talk to me about the weather, I always feel certain that they mean something else–Oscar Wilde

It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing–Elmore Leonard

As a man gets wiser, he expects less, and probably gets more than he expects–Joseph Farrell

Was there ever a wider and more loving conspiracy than that which keeps the venerable figure of Santa Claus from slipping away, with all the other oldtime myths, into the forsaken wonderland of the past?–Hamilton Wright Mabie

Where does the family start? It starts with a young man falling in love with a girl–no superior alternative has yet been found–Sir Winston Churchill

When I stepped from hard manual work to writing, I just stepped from one kind of hard work to another–Sean O’Casey

Every large family has its angel and its demon–Joseph Roux

He who asks a question is a fool for five minutes; he who does not ask a question remains a fool forever–Chinese Proverb

Being “well dressed” is not a question of having expensive clothes or the “right” clothes–I don’t care if you’re wearing rags–but they must suit you–Louise Nevelson

Inspiration always comes when a man wills it, but it does not always depart when he wishes–Charles Baudelaire

Love is a child of freedom, never that of domination–Erich Fromm

Nostalgia is a file that removes the rough edges from the good old days–Doug Larson

It may be that all games are silly. But, then, so are human beings–Robert Lynd

The most beautiful experience we might have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science–Albert Einstein

There are times when sorrow seems to be the only truth–Oscar Wilde

As you get older it is harder to have any heroes, but it is sort of necessary–Ernest Hemingway

You must keep sending work out; you must never let a manuscript do nothing but eat its head off in a drawer. you send that work out again and again, while you’re working on another one. If you have talent, you will receive some measure of success–but only if you persist–Isaac Asimov

One reason I don’t drink is that I want to know when I am having a good time–Lady Astor

A work of art must carry in itself its complete significance and impose it upon the beholder even before he can identify the subject matter–Henri Mattise

So much of what is best in us is bound up in our love of family, that it remains the measure of our stability because it measures our sense of loyalty. All other pacts of love or fear derive from it and are modeled upon it–Haniel Long

Honour makes men faithful in keeping secrets, and therefore unwilling to receive them, for secrets are like red-hot ploughshares. Only saints can walk safely between them–Henry Cardinal Manning

When I meet a new person, I am on the lookout for signs of what he or she is loyal to. It is a preliminary clue to the sense of belonging, and hence of his or her humanity–Haniel Long

So, too, our whole life is an attempt to discover when our spontaneity is whimsical, sentimental irresponsibility, and when it is a valid expression of our deepest desires and values–Helen Merrell Lynd

The history of the past is the story of all truths that man has released–Andre Gide

We find comfort among those who agree with us and growth among those who don’t–Frank A. Clark

When a friend is in trouble, don’t annoy him by asking if there is anything you can do. Think up something appropriate and do it.–E.W. Howe

Nearly all the best things that came to me in life have been unexpected, unplanned by me–Carl Sandburg

A book is a friend; a good book is a good friend. It will talk to you when you want it to talk, and it will keep still when you want it to keep still–and there are not many friends who know enough to do that–Lyman Abbott

The demands of modern living are so exacting that men and woman everywhere must exercise deliberate selection to live wisely–Robert Grant

If you can tell stories, create characters, devise incidents, and have sincerity and passion, it doesn’t matter a damn how you write–W. Somerset Maugham

It is easier for a father to have children than for children to have a real father–Pope John XXIII

Imagination grows by exercise and contrary to common belief is more powerful in the mature than in the young–W. Somerset Maugham

The suggestiveness of summer!–a word that is so weighted with the fullness of existence–means more to me than any other word in the language, I think–Edward Martin Taber

The most beautiful adventures are not those we go to seek–Robert Louis Stevenson

Every calling is great when greatly pursued–Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

A sense of curiosity is nature’s original school of education–Dr. Smiley Blanton

Whenever people talk to me about the weather, I always feel certain that they mean something else–Oscar Wilde

Success comes to a writer, as a rule, so gradually that it is always something of a shock to him to look back and realize the heights to which he has climbed–P.G. Wodehouse

Nowhere does the unpredictable, the unusual excite such confusion as in that settled institution–the church–David Grayson

I thought that nature was enough, till human nature came–Emily Dickenson

No good work is ever done while the heart is hot and anxious and fretted–Olive Schreiner

Description begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s–Stephen King

If only one could have two lives: the first, in which to make one’s mistakes, which seem as if they had to be made; and the second in which to profit by them–D.H. Lawrence

The primary duty of literature is to tell us the truth about ourselves by telling us lies about people who never existed–Stephen King

The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science–Albert Einstein

We must learn how to handle words effectively; but at the same time we must preserve and, if necessary, intensify our ability to look at the world directly and not through that half opaque medium of concepts, which distorts every given fact into the all too familiar likeness of some generic label or explanatory abstraction–Aldous Huxley

You never realize death until you realize love–Katharine Butler Hathaway

Very often, a change of self is needed more than a change of scene–A.C. Benson

One day in retrospect, the years of struggle will strike you as the most beautiful–Sigmund Freud

There are certain things that grab people in a song; in the business we call them “hooks.” You can’t look for hooks when you’re writing, they just happen to come about. You can recognize them only when they’re done–Burt Bacharach

Almost anyone can be an author; the business is to collect money and fame from this state of being–A.A. Milne

I never had to choose a subject–my subject rather chose me–Ernest Hemingway

Substitute ‘damn’ for every time you’re inclined to write ‘very’; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be–Mark Twain

Good friends, good books, and a sleepy conscience: this is the ideal life–Mark Twain

I have never let my schooling interfere with my education–Mark Twain

The things we do at Christmas are touched with a certain extravagance, as beautiful in some of its aspects, as the extravagance of Nature in June–Robert Collyer

Our life is so dependent on our relations with women–and the opposite, of course, is also true–that it seems to me one must never think lightly of them–Vincent Van Gogh

The first fall of snow is not only an event but it is a magical event. You go to bed in one kind of world and wake up to find yourself in another quite different, and if this is not enchantment, then where is it to be found?–J.B. Priestley

Love is but the discovery of ourselves in others, and the delight in the recognition–Alexander Smith

Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate–John F. Kennedy

Almost all words do have color and nothing is more pleasant than to utter a pink word and see someone’s eyes light up and know it is a pink word for him or her too–Gladys Taber

Old houses, I thought, do not belong to people ever, not really, people belong to them–Gladys Taber

Do not protect yourself by a fence, but rather by your friends–Czech Proverb

The great difficulty in education is to get experience out of idea–George Santayana

If you get an impulse in a scene, no matter how wrong it seems, follow the impulse. It might be something, and if it ain’t–take two!–Jack Nicholson

It would seem that you don’t be having any good luck until you believe there is no such thing as luck in it at all–Irish proverb

Weep if you must, parting is hell. But life goes on, so sing as well–Joyce Greenfell

It is beautiful to watch a fine horse gallop, the long stride, the rush of the wind as he passes–my heart beats quicker to the thud of the hoofs and I feel his strength. Gladly would I have the strength of the Tartar stallion roaming the wild steppe; that very strength, what vehemence of soul-thought would accompany it–Richard Jefferies

Reflection: Wisdom’s best nurse–John Milton

Let us not seek the Republican answer or the Democratic answer, but the right answer. Let us not seek to fix the blame for the past. Let us accept our own responsibility for the future–John F. Kennedy

It is better to walk alone, than with a crowd going in the wrong direction–Herman Siu

A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they will never sit in–Greek proverb

Lust is more abstract than logic; it seeks (hope triumphing over experience) for some purely sexual, hence purely imaginary, conjunction of an impossible maleness with an impossible femaleness–C.S. Lewis

Perfection never exists in reality but only in our dreams and, if we are foolish enough to think so, in the past. But the notion of perfection is very real and has tremendous power in disparaging whatever is actually at hand–Dr. Rudolf Dreikurs

Vacations, no matter how long they last, always seem too short–Jean Gautier

If a cluttered desk is a sign of a cluttered mind, what, then is an empty desk a sign(of)?–Albert Einstein

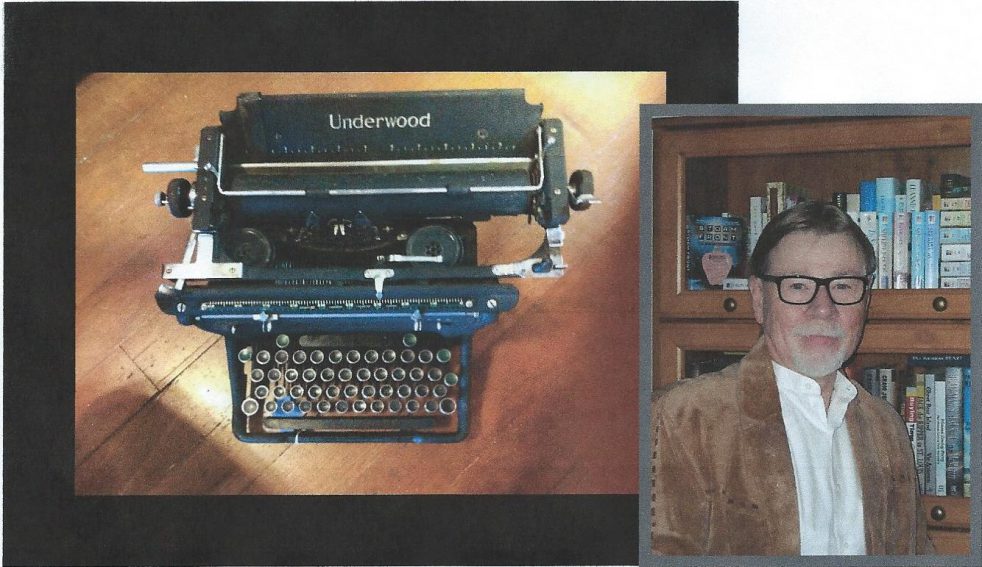

There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed–Ernest Hemingway

There are several good protections against temptations but the surest is cowardice–Mark Twain

The art of our time is noisy with appeals to silence–Susan Sontag

The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of the blessings. The inherent blessing of socialism is the equal sharing of misery–Winston Churchill

The choice between life and death is ever-recurrent. In varying forms it appears whenever a new adaptation is needed or a new potential is ready to be born–Frances G. Wickes

The tragedy of old age is not that one is old, but that one is young–Oscar Wilde

There are three hard and fast rules to writing. Unfortunately, nobody knows what they are–W. Somerset Maugham

A writer is a world trapped inside a person–Victor Hugo

Literary criticism is constantly attempting a very absurd thing–the explanation of (a) passionate utterance by (an) utterance that is unimpassioned: it is like trying to paint a sunset in lamp black–John Davidson

Anybody who thinks that war is pleasant…you know, the old veteran stuff. You know, “War is great stuff.” Well, it’s great for the survivors–not great for the people who are killed in it–Bernard B. Fall

(P.S. Though I respect Mr. Fall’s view, the aftermath of war isn’t always so great for many of the survivors either. I salute you all–GRM)

If there is anything that a man can do and do well, I say let him do it. Give him a chance–Abraham Lincoln

You don’t write because you want to say something; you write because you’ve got something to say–F. Scott Fitzgerald

We choose our joys and sorrows long before we experience them–Kahlil Gibran

A person who publishes a book willfully appears before the populace with his pants down…. If it is a good book, nothing can hurt him. If it is a bad book, nothing can help him–Edna St. Vincent Millay

If you tell the truth (about everything), you won’t have to remember anything–Mark Twain

The Sabbath is what you make of it–a holy day, a rest day, a sports day–or, if you’re not smart, another work day–Herbert L. Goldstein

We do the best we can and hope for the best, knowing that “the best,” so far as selling goes, is a matter of chance. The only thing that is not chance is what one asks of oneself and how well or how badly one meets one’s own standards–May Sarton

The reward of friendship is itself. The man who hopes for anything else does not understand what true friendship is–Saint Aldred of Rievaulx

The habit of courtesy, when once acquired, is almost impossible to get rid of–Robert Lynd

Unlike the architect, an author often discards his blueprint in the process of erecting his edifice. To the writer, a book is something to be lived through, an experience, not a plan to be executed in accordance with laws and specifications–Henry Miller

Without a family, man, alone in the world, trembles in the cold–Andre Maurois

You know your day is going to be a challenge when you start it by dropping your mascara wand in the toilet–RA Miller

Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read– Groucho Marx

We may all have come on different ships, but we’re in the same boat now–Dr. Martin Luther King

Fine fatherly wisdom. Makes me wonder what I’m teaching my sons. Maybe I should ask, but I might fear the answer.

LikeLike

Just remember: honesty, though sometimes overwhelmed with excessive TMI, remains the best policy…something that works both ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person