This is a long one, folks. I initially composed this expose in 2002. The original version was later published in the United Disabilities Association magazine, Kaleidoscope. Although I changed many participants’ names, the events and coincidences portrayed are real. My intent in writing the piece was not to seek sympathy, but rather to illustrate what I and other folks with disabilities endure and what we are capable of overcoming in order to maintain otherwise normal, productive lifestyles. Following my diagnosis, I never attempted to conceal who I was or use my disorder as a crutch. I didn’t want or expect to be treated any differently than anyone else. Every employer I worked with knew about my epilepsy before they agreed to hire me. In turn, I always rewarded employers by giving more than was required when performing my duties, which they recognized via awards and superior performance evaluations. Overall, because of the support and opportunities I’ve been given, my life has been a success, which is what I wish for all people dealing with disabilities.

Thanks for stopping by.

Epilepsy: 101

1967, my senior year in high school. I leaped into the brisk, late-spring air to snag the ball—then the world went black. I regained consciousness as I rolled to a halt across the dusty, baseball field’s white foul line. My head rang like Notre Dame Cathedral. A few seconds passed before I could focus and rise to my knees. I felt like a foul ball.

The first person I spotted was Bill Cramer, our school’s all-conference defensive lineman. Butt on the ground, hands cupped over his mouth, Bill was writhing in pain. Because he’d been airborne when I jumped to catch the football, it dawned on me that Bill and I must have collided––just before my lights went out. Oh shit, Coach is gonna be pissed if I damaged one of his prize athletes. Especially two days after Bill got his front teeth fixed.

Still a bit dizzy, I wobbled to my feet and walked toward the whining guard. Coach Carson arrived just before me.

“Are you all right, Bill?” I said.

With his dark-framed glasses askew, Bill moaned something I couldn’t understand. For the moment, his “tough guy on the line” mantra from the yearbook didn’t quite match.

“Give him some room. Let me check it out,” Coach commanded.

By this time, the rest of the guys in our P.E. class had gathered around the injured football hero. One of them behind me said, “What’s going… Oh God, what happened to your head?”

I turned and noticed that my classmate’s wide-eyed gaze was directed at me, not Bill Cramer. But why? Except for a few clanging bells, I was okay. After raising my hand to the back of my head, I sensed wetness in my hair, lukewarm at first, but cool as I lifted my palm into the chilly, March wind. A deep crimson coated each finger. Dripping onto the dirt, the thick red liquid formed tiny mud pots in the dust that poofed into the air.

“Jesus,” Coach said when he spotted my bloody mitt. Coach Carson’s resemblance to Curly from the Three Stooges was uncanny. As if he’d accidentally smacked Moe in the face with a 2X4, his startled expression appeared serious as he bailed on Bill Cramer and scurried toward me. “Hold your hands tight against your head and keep ’em there,” he said. “Let me take a look at that.”

Well which is it, Coach Curly? I’m the one who just got hammered, but you’re the one who’s talking like it.

I dutifully obeyed the first directive and pressed my palms against my noggin until Coach Carson stepped to my aid. He carefully withdrew my hands and immediately pushed them back in place. “Keep both hands tight against your head and come with me,” he hollered.

OK, OK, I’m not deaf, just bleeding.

With my elbows extended above my shoulders, both hands pushing hard against my leaking brain barn, and my chin jammed into my chest, I followed Coach Carson to the locker room like a walking crucifix, staggering from the battle arena. An entourage of curiosity seekers from P.E. class flocked behind us.

Summoned by a messenger in gym shorts, the school nurse awaited my entrance. She repeated the ordeal of removing my hands, saying, “Oh yuck,” and then plopped a thick gauze pad in place to plug the gash before instructing me to reapply my self-inflicted headlock. Once I’d satisfactorily resumed the position, she said, “Time to call your parents.”

Mom arrived shortly afterward, received the necessary medical advice from the faculty caregiver, and then we slowly walked to the car. My posture hadn’t improved since dragging off the practice field, but the incident had drawn an impressive crowd of well-wishers outside. As my mother and I exited the building, I spied Bill Cramer still resting in the dirt, rubbing his mouth. For some reason, I reveled in the moment, extended a bloody hero’s wave, and slid into the family auto. Dr. Forman, here we come.

The good doctor duplicated the “let’s take a look at that…oh my…okay, hold that in place” routine and then gathered his sewing kit. By now my blood was beginning to gel, and Doc was able to trim my hair, cleanse the wound, and deliver a shot of Novocain. At first all was well, no pain at the disaster site, just that silly chiming noise ringing in my ears.

But as I lay face down, while our trusted physician performed his best Singer imitation, I wondered about the scratching sound I both heard and vaguely felt. It didn’t take long to realize it was the needle scraping against my exposed skull. Scritch…Scritch…Scritch. Wow, that’s weird.

Dr. Forman chatted like a barber while he closed the gap in my hide. I hoped he spaced the loops evenly––didn’t want any unsightly souvenirs. A double knot jerked my skin, followed by a scissor’s snip, snip. All done. One more bandage, and I was “good as new.” Except for those damned bells.

“Go home and get some rest, but don’t go to sleep,” Dr. F advised. “You might want to take off from school tomorrow, so your mom can keep you under observation. It’s possible you may have suffered a concussion. I’ll write an excuse for you.”

Wait, I’m confused. Aren’t sleeping and getting some rest the same thing? But hey, your second edict is okay. What do you mean by “concussion?”

After a day’s respite, my return to classes afforded me the welcomed attention of an injured soldier returning from battle. Having survived the ordeal and bearing the gauze medal pasted to the back of my skull to prove it, I was happy to relate––especially to the girls––the tale of my conflict and suffering. It seemed as if the entire student body had been alerted to the incident. War wounds were always exciting. But the novelty of my Purple Heart soon waned, and it was back to the scholastic routine.

Several months after the sutures and bald spot had disappeared, I experienced my first petit mal seizure. As if someone flipped off the switch on a motorized toy then flipped it on again, I froze then resumed action seconds later. A momentary darkness comparable to a long wink, and I was back. Except for the totally blank sensation, while I recognized where I was and what I was doing, I felt fine. These lapses typically occurred when I was shy on sleep or encountered a more stressful situation, which sometimes meant just getting out of bed. Otherwise, the problem remained dormant. I lived life as normal as anyone.

The telltale signs of these brief episodes presented themselves consistently. At the onset, I’d sense mental and physical pauses. A shudder coursed throughout my body and my limbs jerked. Besides the empty, stupid feeling, the conclusion to these mini fits was most often recognized when an object I’d been holding fell to the floor with a resounding crash, splash, or thud, followed by a four-letter expletive that always indicated, “I’m back.”

My mother was the first to connect the coincidence between my short-term outbursts and less than forty winks. She branded me with a condition she labeled the “dropsies.” Since lack of sleep was most often attributed to the malady, the remedy was obvious, and my symptoms were ignored. The only preventive medicine I swallowed was Mom’s ready reminder to get to bed on time. Though I knew she was right, I was still a teenager, whose intelligence level and comprehension of life was far superior to any adult––especially my parents. As an adult and a parent, however, my song and dance would take on a different interpretation.

Throughout college, a regimen of late hours and more frequent jaunts to the liquor store encouraged my condition, but not to the extent of increased attacks. Because the only person who depended on me was me, my stress level decreased. I seldom noticed any problems––at least medically. Perhaps the opportunity to sleep in more often after long nights made the difference. Alcohol, however, failed to be a benefit.

We humans have been informed that booze kills cerebral cells, but that we’re fortunate enough to have thousands of those rascals to spare. Good thing, I suppose. Otherwise, Anheuser-Busch and Jack Daniel’s would have folded long ago. On the other hand, perhaps the public’s gradual deterioration of gray matter is what continues to bolster the numerous brewers’ and distillers’ profits. Either way, when folks like me have a brain that’s already prone to short-circuiting, repeated applications of whiskey, wine, or beer won’t improve electrical receptor performance. Unfortunately, it took me quite a while to fully comprehend that theory.

The next step in my medical excursion occurred when grand mal seizures knocked at my neurological doorstep. I passed out from apparent exhaustion while sitting on the toilet, but no one witnessed the event. With pants around my ankles, it was quite obvious why I was in the bathroom, but I had no concept of when I’d arrived or if I’d even finished what I initially set out to do. Unlike a typical wino, I hadn’t just sagged into a corner, I fell to the floor. Waking up from grand mal seizures felt like a painful, drunken stupor (a perspective I’d learned while at the university) and required greater time to recover. Total helplessness, resulting from temporary amnesia, best described the mood. Every bodily sense was taxed until I could recall my identity and location once more. The reason for being where I was often challenged my brain a bit longer.

In reflection, the events prior to this point, and the way they unfolded, seemed almost comical, particularly the ordeal with Coach Curly. The day I took my first ambulance ride altered that perspective.

In the spring of 1976, nine years from my memorable, high school headbutt, I suffered one of many violent episodes. Now married, with one son underfoot, and another bun in the oven, I shocked my young family by displaying my disorder for the first time.

My wife and I were preparing for work via our one and only bathroom, packing lunches, and gathering the necessities our boy required for the babysitter. While I completed my turn at the bathroom mirror, my wife and son finished up in the kitchen. She said that she heard a loud thump and nothing more, as if someone had dropped a heavy sack. After calling to me several times with no response, she investigated. Upon her approach, my wife heard shuffling and low, guttural noises that reminded her of a growling dog. The tone frightened her, but not as much as the scene she encountered.

I lay on the floor, shaking, stiff, growling, and bleeding from my mouth. Fortunately, my wife quickly recovered from her initial horror, grabbed a washcloth, and managed to stick it between my teeth. Although she had never dealt with anything like this before, instinct replaced shock. She knew what she had to do and didn’t hesitate. Grabbing our equally horrified son’s hand, she escorted him to the living room and made him promise to stay on the couch. Then she called 911.

The calming voice on the other end of the phone restored some order in my terrified spouse’s mind. The dispatcher instructed her to avoid attempts at restraining me but to try and prevent further injury––a rescue team was on the way.

Sirens blared as I faded in and out of consciousness. Lying on my back with a hissing, plastic dome strapped across my face, I heard voices but comprehended nothing. My body jostled back and forth, up and down. My head rocked side to side. I was going somewhere, but not in a limousine. I stared through foggy images of the vehicle’s cramped enclosure with figures darting about. Where am I? Is this a dream––a nightmare? Who keeps talking to me? I don’t recognize the voice. Man, I’m tired.

At the ER entrance, I began to understand what was happening, but still didn’t know why. The EMTs wheeled me from the ambulance into the building, chatting along the way to insure I was coherent. But I wasn’t really. What did I do to end up at the hospital? Was I involved in an accident? I don’t remember anything. Where’s my wife and our son? Are they okay?

An assortment of people wearing scrubs hovered over me. I heard one verify that my vital signs were stable. Another technician penetrated a vein––OW! This definitely isn’t a dream. She filled several vials with blood. Doctors and nurses fired question after question. I responded to them all and hoped my answers were correct. The administrators looked grim and I didn’t want to fail this test. Why can’t they use multiple-choice answers? I always do better with multiple-choice.

Finally, a familiar face entered the room. Our family physician sported a grin, along with his most cordial bedside manner. And why wouldn’t he smile? He’d surely be well paid for this adventure. Dr. Farley scanned the chart at the foot of my bed and asked, “How are you?”

Well, obviously, not too well, goofball, otherwise I wouldn’t be lying here. “Not so good, I guess,” I replied.

“How come you’re in here?”

Oh, I happened to be in the neighborhood, just thought I’d stop by. Geez Louise. “I don’t know. I was hoping you could tell me.”

My wife entered the cubicle, a skeptical smile on her face. Dr. Farley informed me of the grand mal seizure and that I was going to be a guest of St. Francis Hospital for a few days, so he could keep me under observation and run a few tests. Then he reviewed the list of experiments I’d undergo.

I nodded agreement. I just wanted to get on with it and go home. Although I appreciated their purpose, I didn’t care for hospitals––or the implications of the tongue depressor, wrapped with fifty-yards of adhesive tape at my bedside.

Next the good doctor questioned my genealogy. Except for hangover-induced jitters during college, I couldn’t recall either of my brothers or anyone from my side of the tree having suffered convulsions. I glanced at my wife and closed my tear-filled eyes. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s all right,” she replied.

But I knew it wasn’t.

“What about head injuries?” Doc Farley inquired. “Have you ever suffered any head trauma?”

BINGO! I related the golf club to my left frontal lobe when I was 5, tripping and smacking the back of my skull on the concrete when I was 11 or 12, jamming my noodle into the family car’s door frame about that same time period, and, of course, the mighty whack in high school PE.

“Ahhhhhh,” Doc Farley said.

So, I stuck out my battle-worn tongue, the one that coordinated with my weary ego.

He shook his head. “No, no. I meant that your head injury could be the cause of all this.”

“Ogh, OghKgh,” I mumbled and retracted my tongue.

In response to my actions, my wife rolled her eyes and issued a weak chuckle. Her focus tracked toward the ceiling. She couldn’t believe I’d responded he way I had. Observing each other’s reactions rewarded us with a glimmer of hope.

“Well, let’s get you settled into a room and schedule a couple tests for this afternoon,” Doc Farley said. “I’m going to bring in a neurologist to make sure we get to the bottom of your illness as quickly as possible.”

“Okay, fine.”

Except for the probes the lab technician jammed into my cranial exterior––skin that was only intended to support the weight of tiny hair follicles–––and the gooey pads he glued to my chest that threatened the few curly representations of my manhood, EEG’s and EKG’s, weren’t too bad. The spinal tap, on the other hand, proved to be a totally different barrel of laughs.

Oddly enough, the gentleman that prepared to stab me in the back and claimed to be a neuro-specialist was Dr. Bill Cramer. The same handle as the star athlete whose dental imprint on my skull had apparently initiated this fiasco. I wondered whether the entire affair wasn’t a sadistic dose of karma. Both my past and present family doctors’ last names began with F and now the Cramer thing. What were the odds?

Following a local anesthetic, Doctor Cramer had me scrunch into a fetal position, then he initiated the procedure. “Hold perfectly still,” he said and dove in with both left feet. I got the immediate impression that––except for medical school cadavers––I was Doctor Bill’s first dance. The experience felt as if he tried to wedge a sequoia between two of my lumbar vertebrae. A misguided Mack truck rumbling over me would have been more enjoyable. After several attempts, Dr. Bill hit me with another surprise.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Miller, I know this is uncomfortable.”

“Ugh.” You have no idea, Doc, and you did your best to prove that.

“I’m not able to obtain enough fluid for testing. We may have to try again later.”

“Ugh-uh.” Not in your lifetime, Bozo. Take your clown act somewhere else.

After relaying my experience to Doc Farley, he deemed the need for another go-round with Bill the Butcher unnecessary. Instead, he opted for X-Rays, using a metallic pigment injected into my bloodstream, as the final examination. The procedure itself wasn’t painful, but the after-effects nearly did me in. Following the radioactive photo session, my doctor and the lab tech cautioned me to remain prone for several hours. “Because of the dye, standing upright could give you a throbbing headache.”

Boy, was that an understatement.

With the decathlon of medical investigation and diagnostic summation concluded, Doctor Farley handed down the verdict. I had epilepsy, induced by severe head trauma.

I considered my brand-new label. Jokes about spastics suddenly took on totally different meanings. Now, I was one of the minorities those jokes made light of––some told by my best friends. “Oh.” Thanks, Doc, got any good news? “Can I go home now?”

I left St. Francis that afternoon. My head pounded as if it were being hammered and squeezed in a vise. No amount of Tylenol or Excedrin could suppress the thumping. The pain would have to wear off, which seemed to take forever. Prior to my departure, Dr. Farley instructed me to take it easy––once the pounding ceased––gradually slip back into my daily routine, use more precautions, and, “Don’t forget to take your medication.”

But what the hell? I was a young man in my mid-twenties, racing down the highway of life, and picking up speed. Now I was supposed to jam on the brakes? How was I supposed to deal with a permanent-affliction anchor chained to my back bumper? On the other hand, the finish line was way off. After this brief pit stop, I could stomp on the accelerator again, right?

At first, friends and relatives didn’t know exactly how to approach me. It was as if I had a big, foreboding E tattooed on my forehead. I felt like Hester Prine with her scarlet A, except I wasn’t wearing a cloak I could toss aside. I had epilepsy. No one, including me, knew when I might have another fit and bite myself––or somebody else. When asked about my condition, I often took advantage of that very concept by informing people that’s exactly what I’d do. The look on their faces after my threatening admission was MasterCard material––priceless. But so what? It didn’t change anything.

Symptoms of an oncoming attack remained the same: shudders, momentary lapses, the dropsies, and then POOF. The next thing I recognized was that I was lying down, with my wife or someone who cared by my side, assuring me it was okay. But it never was. Eventually, I’d realize what had happened––again. The only thing I could do was to close my eyes and rest. Tears of disappointment often trickled down my cheeks, or I cursed––or both. My wife said I’d usually bear a crazed, terribly confused and frightened expression when an episode was near. I learned to trust her judgment because she was the one who witnessed my violent tremors far too often. I’ve been so blessed to have her with me, and so very sorry I burdened her with it all. My consolation: I knew our love was real.

Since my diagnosis, neuron sparklers have bounced haphazardly inside my skull on numerous occasions. Sometimes the aftermath was nothing more than a headache and a tremendous desire to sleep. More often it wasn’t. On rare instances, I managed to talk my way around a seizure without consequence. The positive tally there, however, was minimal.

During this time period I took a few more ambulance rides, scared hell out of people I loved, and suffered more lumps and stitches. Because of a chipped molar, I also took up the art of tongue piercing long before it became vogue. This was perhaps the nastiest side effect of my attacks. It’s said that, pound for pound, the tongue is the strongest single muscle in the human body. After running mine through an unconscious, molar-powered meat grinder, however, I guarantee it’s not so tough. Following a nasty episode, eating and talking became routine pleasures I could not enjoy. The burning punctures were excruciating and could take weeks to heal. Communication was painfully frustrating at best. Thank God for dental caps.

Thankfully the art of medicine has progressed in leaps and bounds. MRI’s and C-T scans have superseded the not quite obsolete X-ray machine. And, unless you’re claustrophobic, an MRI or C-T scan is quite painless. I know because I’ve utilized those resources several times.

After a head-bashing collision with a desk in 1997, I began multiple, grand mal episodes. In turn, I discovered a neurologist who actually listened to me. What a blessing. Dr. Bailey restructured my medication intake, which remarkably improved my situation. He also prescribed a quick dissolving sedative I could place under my tongue if I felt a seizure approaching. That added option detoured serious tremors on many occasions, but not all. Thanks to Dr. Bailey’s guidance, I also learned that an occasional beer or glass of wine in the evening was not an unforgivable sin, as long as I paid strict attention to administering my medication and afforded my body the opportunity for adequate sleep. A night without the prescribed seven to eight hours under the covers became a rarity. Best of all, I’d broken a trend. My new neurologist’s first name wasn’t Bill, and his last name wasn’t Cramer, plus my family doctor’s name didn’t begin with an F. But there was one more thing I had to conquer.

Stress represented the final obstacle toward a more stable, healthy condition. Unfortunately, I worked in a fast-paced, high-anxiety job––at least for me––that frequently pushed the envelope. My exposure to a near constant-pressure environment compromised body-restoring rest. Although I got to bed on time, my mind frequently wouldn’t let go and either wrestled with the previous workday’s events or failed to relax trying to prepare for the next one. I didn’t sleep and might just as well have been running a marathon.

Enter Y2K, not only a noteworthy period for computers, but also a mementos time in my family’s life. Our oldest son married in April, our youngest son left for college in May, and my father passed in August. In between these events, I suffered another nasty seizure.

Dad’s death also inspired an awakening for my wife and me, a decision that would forever affect our lives together. Following the onset symptoms of another seizure, my wife said about my job at the time, “I want you out of that place. If you keep working there, it’s going to kill you. I love you dearly, but I can’t––I won’t stay around and watch that happen.”

Her mood was undaunting, her proclamation absolutely correct. Her tough love slapped me to a reality that caused me to focus on what truly mattered. My salary was meaningless without my health––non-existent if I was dead. So, in October 2000, I left my job. My wife and I sacrificed my paycheck so that my disorder might embark upon more extensive vacations. My attitude, and my entire outlook on life reflected a positive change. My mind and body became more at ease, more liberated to explore entirely new life avenues. Though the alteration proved to be a major relief, it also presented financial difficulties, but we formulated a plan.

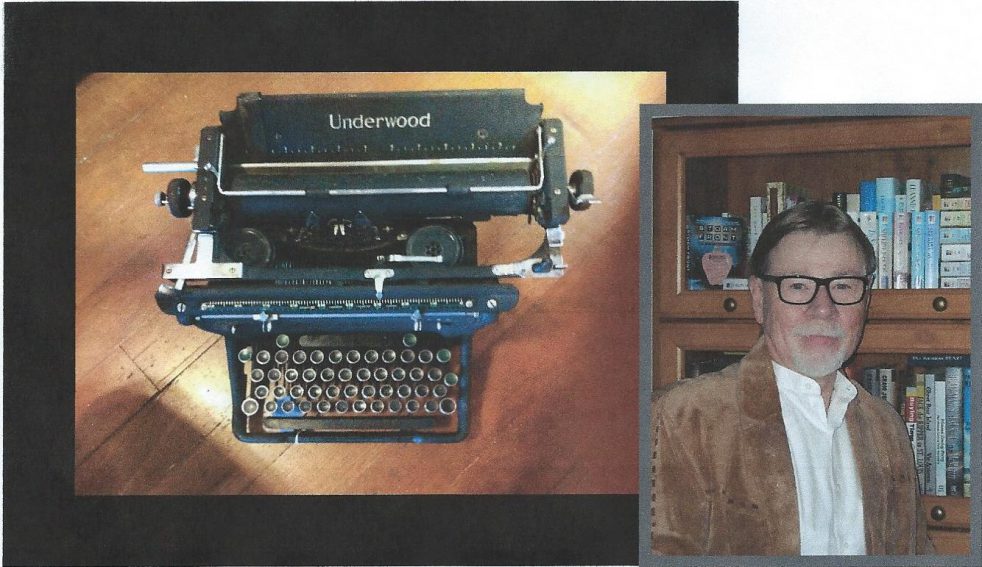

I began writing and, in 2001, accepted a job with the National Park Service as a seasonal Ranger, two occupations I instantly loved and should have considered pursuing much sooner. After all, how many people could honestly say they looked forward to going to work each day? I could, and my family immediately noticed my metamorphosis. Because of these substantial life choices, I smiled and laughed more often. I became a better man––a better husband, father, and friend. Though epileptic events continued to taunt me, they remained fewer and much farther apart, most often linked with some other form of illness.

In 2010, however, I experienced a seizure while working at the National Park––something that, because of my favorable environment, I thought would never occur. Fortunately, I recognized that the episode was inevitable and called the park dispatcher. Within minutes help arrived––and just in time. But having a grand mal seizure in the park hurt me emotionally. I was in the next best place to heaven itself and had failed to control my disorder.

In 2011, I began experiencing sensations similar to the auras felt prior to a seizure. Some of those events resulted in the real thing; many others were false alarms. But the situation persisted which eventually led to a major seizure in the ER, another hospital stay, plus more MRI’s and tests that prompted an additional diagnosis: I also had a blood-clotting condition. Part of the issues I’d recently faced were related to inconsistent blood flow to my brain as well as the rest of my body. Blood thinners joined the regimen of anti-convulsive drugs as part of my daily routine. Fortunately, the two medications played well together. For two years, I remained seizure free and, in 2012, retired from the Park Service.

In 2013, I had long overdue knee replacement surgery. Because of the physical trauma associated with the surgery, I experienced another seizure, which doctors said was not uncommon for a person with my disorder. Although it was good to know there was some sort of logical correlation, I couldn’t help feeling disheartened.

Fast forward to July 2019: I’d completely sidestepped the ugly experience of seizures for six years until a back injury provided the sort of body trauma that instigated another episode, another ambulance ride, and another hospital visit that included more examinations and tests. A new neurologist who expressed both concern and understanding, plus a recommendation for revised meds, offered renewed hope. So far, so good. Still, the demon I thought I’d finally conquered had arisen like a Phoenix to harm me once more, and it hurt. Having my granddaughter witness the event only made it worse.

Thankfully, God continues to bless me with the woman who’s remained at my side and shared my disorder for forty-seven years. Without hers and our family’s support, I’m not sure I’d have endured this long. Because of them, however, I never allowed my affliction to inhibit me from doing what I wanted or needed to do.

Epilepsy will remain with me until I’m no longer around to discuss it. For the duration, I’ll need to remain positive and mind my P’s and Q’s regarding alcohol, sleep, stress, and medication. But I have help. Before bedtime my wife seldom fails to ask, “Did you take your pills?”

Most often I reply, “Yes, I did,” and then smile and kiss her goodnight. Some men––women, too––might be offended by the implied forgetfulness. But you know what, I’ve learned that I can live with it.

A few days ago my best friend had an epileptic seizure for the first time in her 71 years. After tests and a short hospital stay they discovered a benign tumor in lining of her brain. She is at home now with medication rather than surgery as the medical plan for dealing with it. But how to deal with it emotionally is her biggest struggle. I found a lot of information and supportive insight in you writing. I will pass it on. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Thanks, Stephanie. Knowing that relating my experience may help even one other person makes me feel very good. My best wishes to you and your friend.

LikeLike

Gary, thanks for sharing your story. It is a great article and we couldn’t stop reading. You are an inspiration to everyone, as we face our own limitations.

Den and Sue Brunner

LikeLike

Thanks, Den and Sue. The piece started as part of a writing exercise that my instructor said I needed to finish without bailing on the truth. Though it was difficult to face the realities, it was also a necessary step I had to take. Glad I did. Glad the piece inspired you.

LikeLike

Thought you might be interested

LikeLike